|

|

|

|

The 'Real' 18th Btn 2nd Div 1st A.I.F. |  |

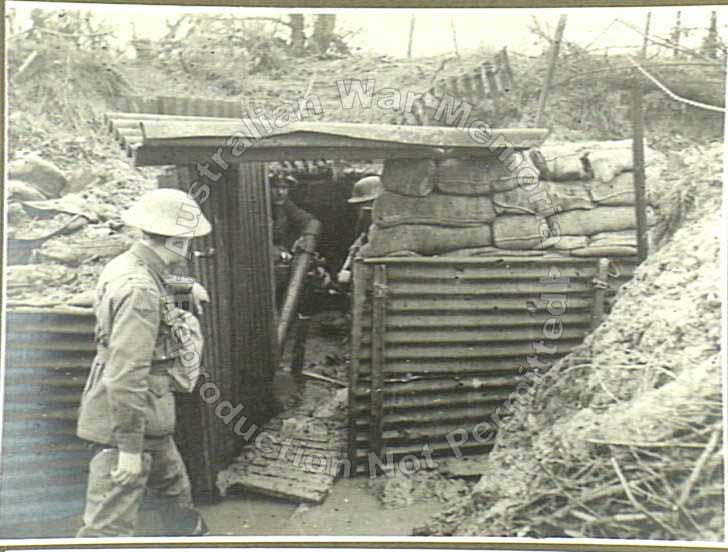

| The 18th Btn 1st A.I.F. A short history. The four companies of the 18th Battalion sailed aboard the converted liner ‘Ceramic’ on 25 June 1915 bound for Egypt via the Suez Canal. The 1st and 2nd Reinforcements had already sailed via separate vessels. However, the real story of the 18th Battalion begins about eight months earlier. In 1914 the actions of a single man twelve thousand miles away had a significant impact on the lives of all Australians for years to come. As a result of Gavrilo Princip’s assassination of the Archduke Ferdinand of Austria the major powers of Europe went to war. Australia’s still close relationship with the mother country resulted in Andrew Fisher’s commitment to raising a force of twenty thousand men. This force sailed out from Sydney aboard the transport vessel ‘Berrima’ on 18 August 1914 bound for New Guinea. Aboard were several men of the soon to be formed 18th Battalion: men such as Captain Cyril Herbert Dodson Lane, adjutant to Colonel William Holmes. Captain Sydney Percival Goodsell was the quartermaster and Lieutenant Rupert Markham Sadler took charge of the signaling section. It was late September when the 1st Battalion AN&MEF arrived in New Guinea and started the task of removing the German presence. Other members of the 18th who took part were Allan Forbes Anderson, Roy Arnold, Basil Blackett, Errol Cappie Nepean Devlin, William Johnston Graham, Nicholas Hamlyn Hobbs, John Bayley Lane, Frederick McGlashan, Bruce McLachlan, Charles George Walklate, Basil Bruce Williamson and Herbert Wiseman. The AN&MEF’s assignment was successful with limited casualties but resulted in those enlisting in the early days did not become members of the AIF until after the Gallipoli landings. The voyage from Sydney to Egypt was uneventful until they entered the Suez Canal and first sighted land. The ‘Ceramic’ held up at Aden with word that the troops would be used in garrison duties to quell a native uprising. This did not take place and the rest of the trip was quiet. After four weeks in Egypt orders were issued to Lieutenant Colonel Alfred Chapman to prepare for embarkation to Gallipoli to reinforce the men already there. The early August assaults on Lone Pine and The Nek had taken their toll and the powers that be still believed a break through was possible. The 18th Battalion arrived on Gallipoli as fresh-faced troops eager for battle. Two days later this was completely shattered and the romantic myth of war was lost forever. Orders were issued almost immediately for the battalion to move up to the front line. Many of the men were not aware that they were to assault Hill 60 until just before 5.00am on the morning of 22 August 1915. Hill 60 was considered of strategic importance for two reasons. First of all it overlooked the much of the Anzac positions and second of all who ever controlled it also controlled two wells that supplied water. Syd Goodsell (now a major) led his company into murderous machine gun and rifle fire and several men were killed. He managed to get his a considerable number of his men into the first line of Turkish trenches before halting. Chapman could see that more men were needed so he ordered the next two companies into the firing line. Captain Alexander McKean (a school teacher from Penrith), part of the second wave, was struck in the shoulder and took no more active part in the war. Cyril Lane (also a major and company commander of ‘B’ Company) lost most of his men before reaching Goodsell attempting to consolidate. One young man, Private Joseph Maxwell, was appointed stretcher-bearer of ‘B’ Company and believed he would not get much opportunity to participate; he was wrong. After failing to make further headway through the day someone gave the order to withdraw although no one knew issued it. Those that managed to survive were shattered with the loss of so many friends and (in some cases) brothers. If those still fit thought that was their first and last experience of total carnage they were wrong. Just five days later the Battalion was ordered back into the line for a second attempt to remove the Turks from Hill 60. Chapman called for volunteers this time and every fit and able man stepped forward. This time they were successful in securing a foothold on the hill but many more men were killed, including the heroic Lane, struck once in the heart by a bullet during a bomb fight with the enemy. The 18th Battalion remained on Gallipoli until the end in December 1915 before evacuating without casualties. Major George Murphy (later battalion commander) transferred from the 20th to the 18th Battalion just after the August debacle. Lieutenant-Colonel Alfred Chapman was relieved and returned to Australia. Evan Wisdom took over as battalion commander but was destined for higher honours. Three months after their return to Egypt they were setting sail yet again this time for the Western Front. They arrived in France on 25 March 1916 almost to full strength and moved into the front line, for the first time in April 1916. The word was that the AIF would only be used for patrolling and garrison duties but during the night of 25/26 June 1916 the 5th Brigade (with members of the 18th Battalion) they made their first trench raid. Captain John Bayley Lane (of the AN&MEF) was the senior officer of the battalion. The following night they did it again. Both raids were successful although one man was taken prisoner, Walter Frick (although not mentioned by name Bean makes reference to his capture). The 18th Battalion (as part of the 2nd Division replaced the weary members of the 1st Division in late July 1916 at Pozieres and suffered just as severely until withdrawn at the end of the first week in August. The acting battalion commander George Murphy was severely wounded during the campaign and did not return until late October 1916. Syd Goodsell fell ill in August 1916 and was evacuated and did not return. It was about this time that the AIF recognised the leadership qualities many of the ‘other ranks’ and started promoting these men to officers. The next major battle the 18th Battalion took place in was Malt Trench in February 1917 after the men went through the worst winter in France for forty years. It was at this time that the first recommendations for Victoria Crosses were made for members of the battalion. Edwin Nipperess and Eric Allsop were awarded Military Medals for exceptional courage in two separate incidents. Five men lay out in the open and Nipperess crawled out, under fifteen feet of wire entanglements and heavy fire, and rescued the three wounded men. They were lying on the enemy parapet and were being systematically fired upon although they were not offering any sort of resistance. He dragged them, one by one, from the parapet into shell holes in the open. He then carried each man across the Bapaume Road, under machine gun fire, back to the safety. He then returned and also dragged the corpses of the other two back to ensure the Germans were not able to identify the battalion that was opposing them. (Nipperess and Allsop were both killed before the year ended.) Before the year ended the Battalion had fought at Bullecourt, Ypres and Passchaendale. 1918 saw an end to stagnate trench warfare as the Battalion started actively patrolling. Joseph Maxwell (awarded a DCM in Ypres as a CSM) was now a 2nd lieutenant and led many of these patrols. He was awarded the Military Cross in March 1918 whilst on patrol. He was collecting intelligence with a patrol of thirty men when he was about to return. As he was covering his party he observed sixty or so Germans entering a trench system nearby. He recalled his men and they attacked the unsuspecting Huns. A brief struggle ensued before the enemy withdrew. The battalion’s only failure (if it could be called that) during their three years on the Western Front took place at Hangard Wood in April 1918. The 5th Brigade where to attack the wood whilst their French allies were to take the Cemetery nearby. The attack started out according to plan but during the following morning it became imperative that the French had to take the cemetery to succeed. This did not happen and the order to withdraw was given. Ironically enough a short while later the French took, and held, their objective. Of the five officers and one hundred and seventy-five men who took part, four officers and about eighty men had been hit during the attack. In May 1918 the battalion was at Morlancourt were one of the most remarkable events took place. On the 17th Lieutenant Alex Irvine was at the front line when he realised most of the men were dozing or asleep. Boyce replied, "The Hun will be asleep, too." This gave Irvine an idea and the following morning he took eighteen men quietly over the parapet and across ‘No Man’s Land. They entered the enemy trenches without a shot being fired and just ten minutes later were returning with prisoners and intelligence. (John Laffin in the Australians At War series wrongly attributed Irvine as belonging to the 17th Battalion). It was becoming quite obvious at this time that the Germans were going to lose the war and launched they final offensive in August 1918. The 18th Battalion was heavily involved in this fighting on 8 and 9 August 1918 with many heroic deeds being performed. The battalion was required to make its way to the jumping off point through thick fog and many men from all battalions lost their way. CSM Albert Dickinson took it upon himself to ensure men of the 18th reached the required destination. Captain John Bayley Lane was recommended for a Victoria Cross for his actions on this day as he displayed outstanding leadership qualities. Yet again the battalion did not receive the highest honour as Lane received a DSO instead. Bill Graham (Boer War, New Guinea and Gallipoli veteran) continued to brilliantly lead his men and continued through these two days before succumbed to wounds (struck in the shoulder and then in the buttocks). Through the month of August 1918 the battalion fought frantically with the enemy trying to regain the upper hand before given the opportunity for a rest. The 18th Battalion took part in their last battle of the war on 3 October 1918 when they were required to take and hold a stretch of the Beaurevior Line near St Quentin. Joseph Maxwell was awarded the military’s highest honour on this day by his excellent example he displayed. Early on in the fighting he assumed command of his company after the commander was severely wounded. He came across wire six belts thick so he worked his way, alone, through it and killed the destroyed the enemy machine gun post before returning and leading his men through it. The fighting was heavy but finally their position was consolidated and prisoners were being brought in. One suggested to Joe Maxwell that there were others who wanted to surrender so he took two men to locate them. They walked into a trap and it was only through a barrage which started was Maxwell able to regain the upper hand and escape. Shortly after the 18th Battalion was removed from the firing line for the final time as the Great War ended just over four weeks later. All copyright on this document is retained by myself and the use of it is permitted only as a page on the 18th Battalion Re-enactor’s web page presently owned by Graham Brissett. No other use is permitted without written consent of the copyright owner. Michael Vickers |

|

|

|

|